Climb 1,000 stairs,

learn 1,000 new words,

see 1,000 new things,

share 1,000 conversations

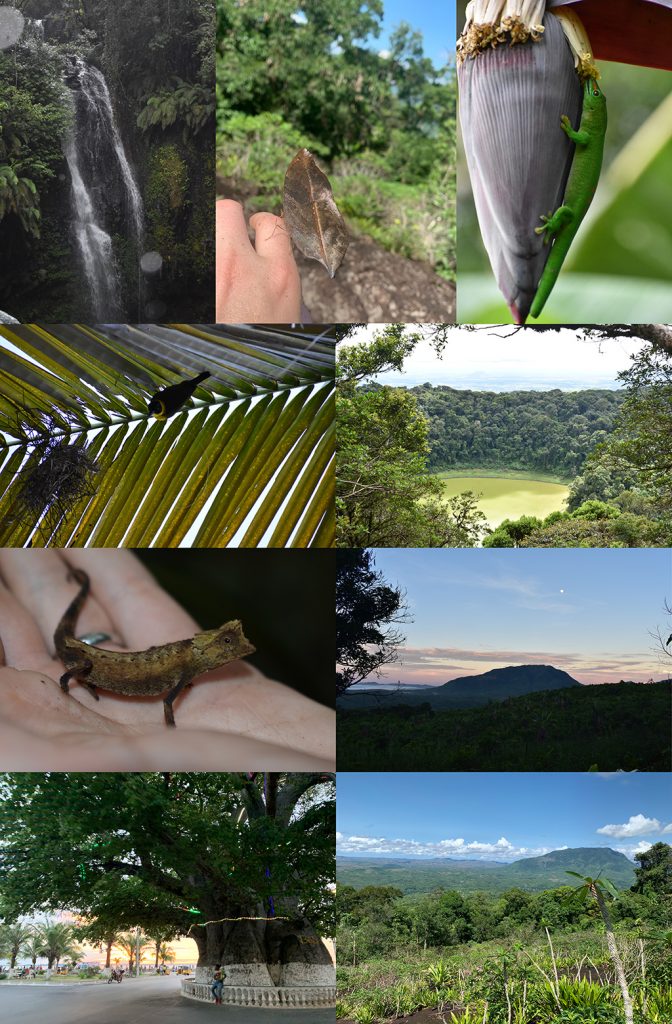

These are all just some of the steps involved in discovering new plant species and understanding plant biodiversity – or at least they were on my most recent trip to Madagascar in search of strange and wonderful plant life.

The idea of 1,000 ascensions came to me on the second day in the field, on our way to Manongarivo Special Reserve – a protected area, managed by Madagascar National Parks in northwest Madagascar. As we came closer to Manongarivo, my colleagues explained a little about the park. In Malagasy, Manongarivo literally means “go up one thousand times” which refers to low mountains and hills that make up this region. If you want to go to Manongarivo, you better be prepared to go up 1,000 times. Right away, I knew we had a long and tough journey ahead of us.

Manongarivo is special for a number of reasons. It is located in a unique part of Madagascar, known as the “Sambirano.” In French, this has been referred to as the “domaine de l’est” because an influx of humidity from eastern Madagascar is trapped by a chain of mountains and carried in a narrow band, westward across the island. This dense, humid air is drawn across the island and interrupts what is otherwise a large dry, deciduous forest that spans the western part of Madagascar from tip to tip, north to south. This influx of humidity interrupts otherwise similar biomes in Madagascar and helps form part of the amazing quilt-like tapestry of habitats that many researchers believe gives rise to the incredible biodiversity we see here. In many parts of Madagascar you can see 100 species in one area, hike 15 miles and see 100 different species that you’d never see in the place you just walked from.

Before I get back to talking about Manongarivo, I’d like to say a few words about what brought me there. I’ve been working in Madagascar for more than ten years and throughout this time I’ve learned almost as much about it as I have about Virginia – the state where I lived for more than 30 years. I’ve always known Manongarivo was a difficult place to get to. Despite being only 17 km from the national highway, it is – as the name implies – on the other side of a lot of hills and valleys. On top of that, the road is dirt – or better yet, mud and slippery red clay (Fig. 1). So why would I want to go there? Well… the story begins, as most stories of botanical discovery do, in a herbarium.

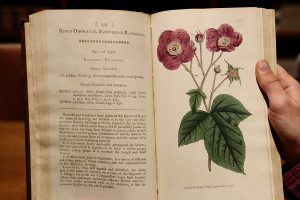

I’ve studied three families of flowering plants in Madagascar, including relatives of ginseng (Araliacaeae), frankincense and myrrh (Burseraceae), and sunflowers (Compositae). Before any fieldwork, you need to understand your study group and you need to have a plan. What is your goal? In my case, it’s to understand and describe species diversity and evolution in one of the world’s hottest biodiversity hotspots. Before you can do this it is important to know the background, who else has studied here? What was their goal? How did they achieve it? Where did they visit and what did they uncover? You can learn this by reading their work and studying the collections they have deposited in the herbaria where they spent their careers (Fig. 2). This is precisely where most species discovery takes place. There is an incredible number of new species in herbaria at this very moment, just waiting for the right person – a specialist – to discover them. This is a big part of what makes any natural history museum such a special place. Their collections include a trove of untapped information.

As a taxonomic specialist, it is essential to understand the group of organisms you study so that you can distinguish one species from another and when you see patterns, you might understand their significance. Work in the herbarium is exciting, fun, and involves navigating a cloud of patterns that are constantly forming, breaking, changing, moving, and shifting until the specialist feels they have a set of reasonable hypotheses regarding what is and is not a species in a particular group. When you find a new species in the herbarium the immediate thing that occurs is that the new species “breaks” an existing hypothesis about what a species is. Your brain wants to put it in a place that it clearly does not belong (with another species) and as you struggle to shift your species hypothesis, sometimes you realize “this thing does not belong anywhere – this is completely different, completely new…”

And so this brings me back to Manongarivo. As a specialist, I have focused on the myrrh genus, Commiphora, and relatives of the sunflower family, Compositae, in Madagascar. Between 1960 and 1963 a French botanist named Henry Humbert at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris published his work on the sunflower family from Madagascar and the nearby Comoro Islands. This work lays the foundation for the study of Compositae in Madagascar. It has guided much of what I do and in some ways lays out a roadmap to diversity in the family. Some of the most interesting species in this family from Madagascar just so happen to grow only in the Sambirano, near Manongarivo. This was also interesting because I have come across two collections of what I know to be a new species in another group that I specialize in Manongarivo. In fact, the species is so different and so out of place here, my first reaction when I saw it was that a mistake had been made. My conclusion was that I needed to visit Manongarivo – if so many new and unique things are here, what else might be uncollected? What other surprises might await a botanist visiting this unique and rarely visited park?

When the day finally arrived to visit Manongarivo, I knew my team and I would be in for a challenge. For one thing all of my colleagues had given fair warning that Manongarivo is not an easy place to get to, much less work in. We visited the local park management office to show our permit and ask for a local guide, bought supplies, and made arrangements for transportation. We were lucky to meet our guide at the park office – the local park manager named “Tsimba”. Tsimba is a good and knowledgeable man who has worked in Manongarivo for nearly 30 years. Tsimba told us he would go to the nearby village to arrange dirt bikes for each of us and explained the dirt bikes would cost 25,000 ariary (about $7 USD) each, one way. If we could not afford the dirtbikes, we could hike 17 km to our base camp – a trip that would take 8–13 hours. Time is money, and when you’re halfway across the world looking for plants your time is especially precious. We thanked Tsimba for his help and made plans to meet early the following morning near the road to the park (Fig. 3).

When we met Tsimba on the following morning he told us he was having trouble negotiating our motocross transport. There were few bikes capable of making the trip and we needed at least five (one for each in our team, plus an extra for supplies). We could only bring one pack of water (9 liters), some rice and beans, and our camping and collecting gear (Fig. 4). On top of that, the bike owners were nervous about the trip, the extra weight, the amount of fuel, and the condition of the roads. Altogether, the price would be 55,000 Ariary per bike, each way. We chose a meeting spot and got loaded as soon as we could. The road looked more like the aftermath of a landslide and riding two-per bike was challenging, especially loaded with gear and going up and down steep, narrow, and crumbling, sliding clay. It took us four hours to go 13 km – occasionally having to dismount, push the bikes, and tighten the fastenings on our gear. We stopped to eat fresh jackfruit about 2/3 of the way. Upon arrival we thanked our drivers for their hard work, paid them, arranged our return trip and introduced ourselves at the village – a quaint, riverside town called Beraty. We hired a porter and a chef, repackaged our equipment for the hike and set off. Luckily we did not have to cross the river by foot (as expected) – a freshly dug canoe with outrigger was awaiting us at the shore and took us across, one at a time. From there, we had a 2 hour hike through the farm and pasture land surrounding Beraty and up to the base camp at Manongarivo. Crossing streams, irrigation ditches, shepherds, and children and families bathing and washing clothes, we made some collections along the way and arrived, exhausted, but ready to set up camp and plan our treks into the park during the following days (Fig. 5).

Talking to Tsimba, we decided on two approaches 1) go directly into the deep forest and collect along the base of the mountain, and 2) hike along a ridgeline as close to the summit as possible. We took the first approach on day one and the second on day two. It’s an exciting feeling to stand in front of a mountain that your research has guided you to, knowing it contains new discoveries (Fig. 6). We set off at sunrise after a plate of rice and beans with “commando” coffee – filtering the grains through your lips as you sip. Almost immediately I saw one of the species I was after – a Commiphora, but sadly it was in a freshly cleared plot of land and was – oddly enough – being cultivated as a post to grow vanilla orchids. My immediate thought was “has this precious new species been removed from the forest and brought to render further destruction to the only habitat where it grows?” Slightly worried, we continued onward and upward, already soaking with sweat in the densely humid and hot forest. We passed a couple from the village who were clearing and planting more of the forest for vanilla (Fig. 7). We expressed our sadness to Tsimba and asked that he please stress to the village how destructive – and fatal – this would be to Manongarivo if continued.

As we continued upward the slash and burn slowly subsided; however, we came to another large, wide opening – a large, wet, and dangerously slippery slab of igneous rock that looked out westward over the valleys of Manongarivo – Beraty village was barely visible as a tiny dot, faraway on the horizon (Fig. 8). Natural spring water and recent rains made this outcrop an ideal habitat for thin layers of algae that betray their slippery hazard – a slip, a fall could be fatal. Choosing our steps carefully we were excited for the strange and different flora that seemed to thrive in this opening – not a minute passed before “Eagle Eyes” Richard spotted a Commiphora growing along the margin. Shouting with joy and excitement – I felt myself disbelieving that myrrh could possibly grow here – in perhaps the most humid forest I’ve ever worked in Madagascar. Myrrh, after all, doesn’t just thrive in dry, deciduous forest, it is an indicator species for dry forest in Madagascar. What on earth is it doing in a dense, humid forest? The small tree was unassuming, stretching and twisting toward the sunlight, it’s leaves large and smooth and the plant itself sterile, unfortunately without flowers or fruit. It didn’t really look much like a Commiphora, but for those who know what they are looking for – it sure enough is. We found a shady spot on our slippery slope, opened our plant press, and got to work preparing our herbarium vouchers. I showed Jacqueline, Richard, and Tsimba the features that define myrrh and explained their ecological affinities, crafting hypotheses on the fly for why and how this species might be here.

Relishing in the glow of this discovery, we continued, carefully, upward. We re-entered the dense forest where no paths existed and fought our way through dense lianas, scrambled over logs, listened to thunder in the distance and the grunts of nearby lemurs. We stumbled upon more clearings along ridgelines that were home to sprawling Begonia with leaves three feet across and parts of the mountain that had cracked apart millions of years ago, revealing what seem like infinite fissures below. Walking carefully we continued to ascend until our bodies were exhausted, our clothes soaking, and our stomachs growling. Tsimba followed the sound of water to a waterfall where we stopped for lunch – some processed cheese, cookies, mangoes, and crackers with Nutella (Fig. 9). Thank goodness for Swiss army knives. The water was cool and a perfect place to relax and get our heart rates back to something resembling a resting pace. It started to rain, slowly at first, and then as the sound foretold, pouring. We took out our rain jackets, packed lunch, and set off again to the other side of the mountain. The rain jacket almost seemed compulsory rather than functional. Have you ever felt so wet that you’re sure you’re head under water in a pool, but standing on solid ground? Where there doesn’t seem to be an end to your shirt or pants and a beginning to your skin?

As we began to descend we came to another slash and burn spot. Along the margin, dense invasive bamboo and grasses choked the path and as we cut our way through our hearts sank to see huge swathes of cleared forest, converted into more vanilla plantation. How long before this mountain is cleared? Arriving soaking wet, exhausted, and with a days worth of collections to process and understand, we huddled in a small wood and bamboo house, put our clothes near a fire to dry, and talked about what we saw and the day ahead. We were asleep before nightfall, whisked away by exhaustion and the sound of thunder and rain.

The next day we were lucky to have a reprieve from the rain. We awoke to a beautiful sunrise and got an early start. For myself, I opted to wear my one extra set of clothing. We were out of bottled water and instead boiled a tea with citrus leaves to bring with us. It was bitter, but pleasantly citric and relieved our thirst. We had a more intense day ahead with higher aspirations. In hopes we might find more of this Commiphora, this time either in flower or fruit, we asked Tsimba to bring us to another rocky clearing. It did not take long and sure enough all along the margin was dotted with this strange species. We were lucky to manage several collections and this time with young fruit (Fig. 10)! This was enough for me to confirm that sure enough, this was the species I had seen so many years ago at the herbarium in Paris – a species I thought impossible because of where it grew and yet somehow here, breaking so many rules I had known about myrrh.

Sore, tired, but joyful, we continued to ascend – we were lucky to collect much Vernonia – a major focus of my work and a beautiful and complex genus of ironweeds. Some of the Vernonia here has an inflorescence (or flowering structure) as big as your hand – just incredible plants and another of my priorities during this trip (Fig. 11). To date the species of Vernonia I was able to collect from here have only been collected 2, 9, 11, and 12 times. Six other collections have yet to be identified. As we leave Manongarivo, my one thought is that I wish I had more time there (Fig. 12). We make our trek back to Beraty village, across the river, and meet our new friends with dirtbikes at the pre-arranged time. One of the dirt bikes needs a repair and another is limping along with a tire that needs a patch. The return trip back takes an hour longer, but seems faster – the thought of a cold bucket shower and a fresh pair of clothes seems as good as the best creature comforts any hotel could offer.

The first five days of the trip were a huge success and – we hope – the hardest part of the trip has completed. From here we zig-zag’d our way northward, visiting other parks and protected areas that seem as strange and remote as though they are from another part of the world, but often only 50 km away. We spent Christmas together in the city of Mahajanga (Fig. 13), sharing stories from the field, talking with our families, and wishing we were home. I’m so grateful to my friends and colleagues who stuck it out with me over the holidays to collect, friends I’ve known for over ten years. After collecting, we return to the capital city, Antananarivo, to organize, prepare, and dry our collected samples (Fig. 14).

If you want to know more about Madagascar and its natural history, check out some of the following resources. Goodman & Benstead’s The Natural History of Madagascar is a great place to begin, just don’t be intimidated by its length – more than 1,500 pages. You can also read about other experiences here from programs such as the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Africa and Madagascar Program, which, thanks to colleagues, has helped coordinate and facilitate my research over the last ten years. Like Missouri Botanical Garden, other programs such as the Kew Madagascar Conservation Centre are working to understand this biodiversity hotspot through conservation, education, and research. If you feel inspired to support this type of work in Madagascar, I encourage you to make a donation and become involved with one of your local natural history museums. Here at BRIT, our botanists and education teams are making strides to advance botanical research, conservation, and education around the world – making stories like this possible through boots on the ground effort and connecting you to stories from the field.

This fieldwork was supported by the Global Genome Initiative (GGI) Rolling Award Program, Award: GGI-Rolling-2020-245.