In the Collection Lens series, BRIT Librarian, Brandy Watts, highlights collection managers from around the world across botanical libraries and herbaria as collections move into the future in an effort to drawn attention to the value of botanical collections and facilitate better understanding and appreciation of their importance and crucial role in preserving and promoting biodiversity data and the vast history of botany.

What is the origin of your interest in herbaria and the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium specifically?

I often say that I grew up in an herbarium. My father, a mycologist, was the founder and curator for 40 years of the San Francisco State University Herbarium. As a child, I spent weekends in the field with my family, and when fungi were not in season, I spend time in the herbarium, helping my dad with his specimens. As a teen I lost interest in the herbarium, but midway through my undergraduate degree, I realized that I wanted a career exploring biodiversity, like my dad. I didn’t want to study fungi, though – I chose bryophytes, specifically liverworts or hepatics, instead. After graduate school, I was offered a one year postdoctoral position at the Steere Herbarium, and I knew when I got there that I never wanted to leave. I managed to stay on and gradually work my way up to Director.

What are the strengths of the Herbarium’s collection?

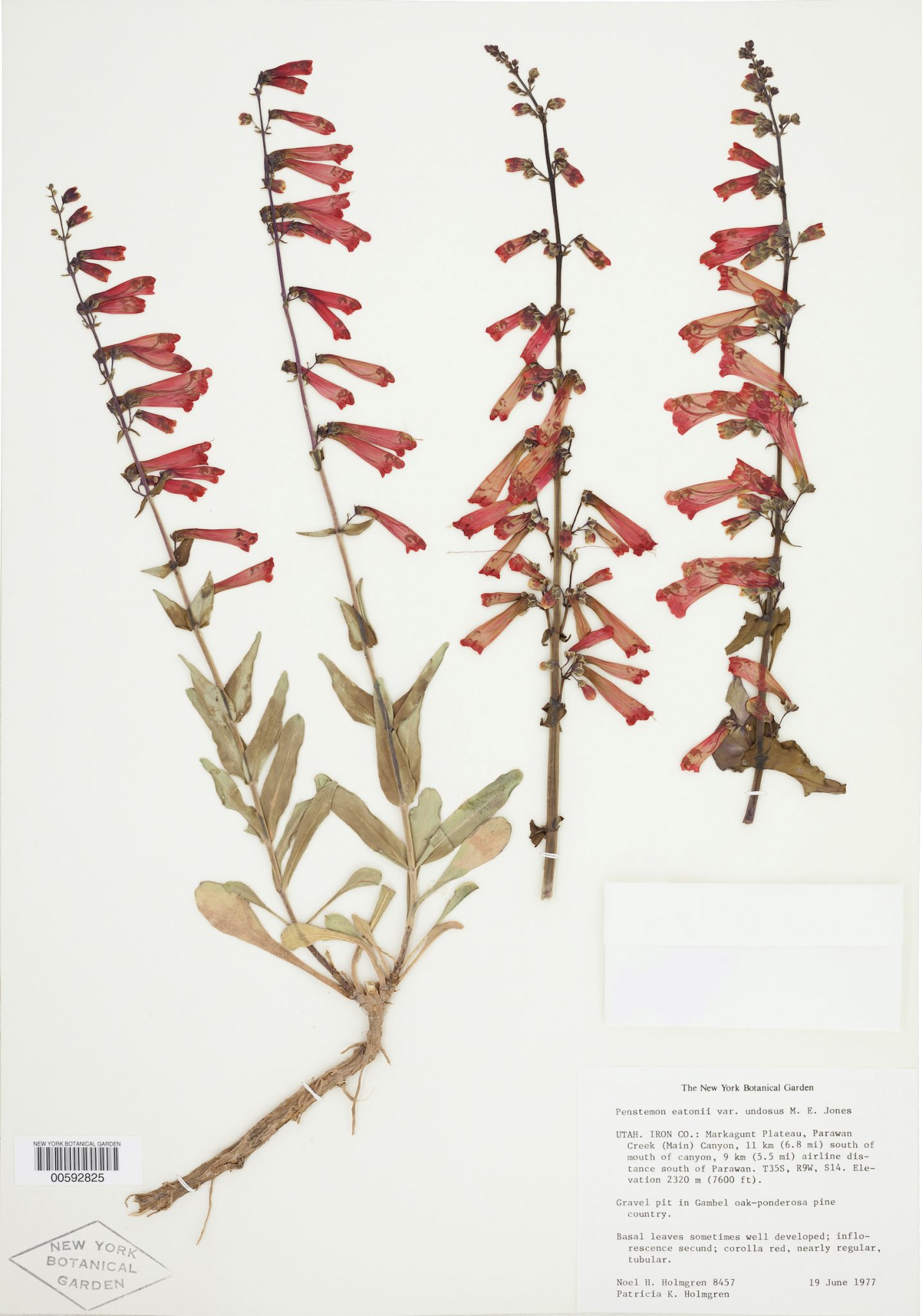

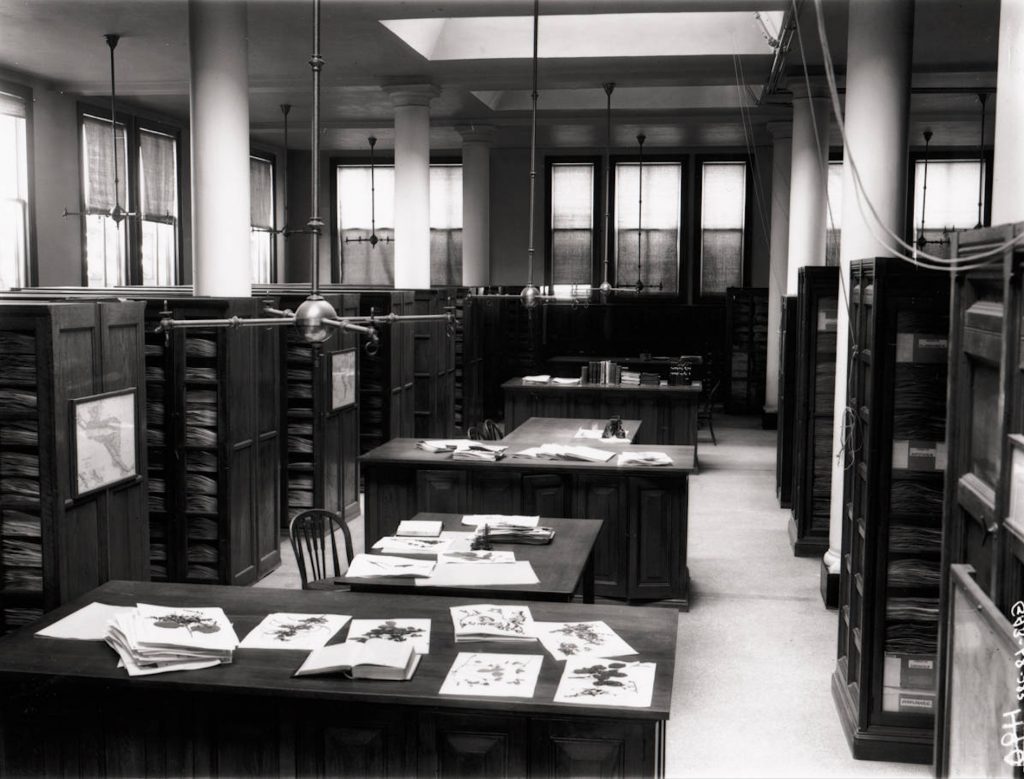

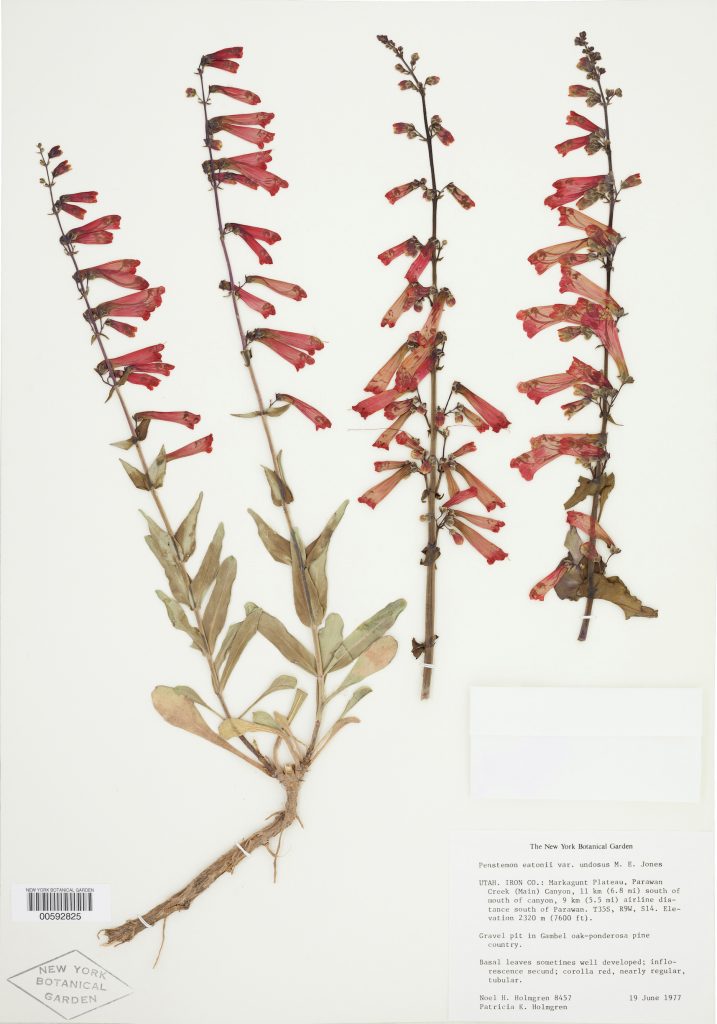

The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium is the largest in the western hemisphere, with almost eight million specimens. The herbarium houses large collections of all groups of organisms that have traditionally been stored in herbaria: flowering plants, pteridophytes, bryophytes, algae and fungi. The geographical strength of the collection is the Americas, with an increase in specimens from Asia and Australasia in more recent years. Within the Americas, we have many historical specimens from the 19th century explorations of the western U.S., as well as more recent specimens from the Intermountain west and the Northeast. We also have very large and important collections of specimens from the Caribbean region and Brazil.

What do you find most interesting about the Herbarium? What is something only you know about the collection?

I never cease to be amazed by the range of collectors that the Steere Herbarium houses. We have the collections of many famous botanists, of course, but I love to learn about the more obscure collectors who have added to the collection—people from all walks of life, who devoted time making collections and saving them for posterity. I don’t know if there is anything only I know about the collection—I probably know as much about collectors of bryophytes in the last two centuries as anyone, though.

At what point during your tenure did you realize that securing funding for the collections was crucial for research, preservation, and access?

I thought relatively little about funding when I first arrived, in the early 1980s. It seemed to me at that time that there was plenty of money for everything we wanted to do! At that time, the National Science Foundation provided what we called “Facilities grants” for large collections that provided extraordinary service to the community, through specimen loans, hosting of scientific visitors, etc. It was when that funding ended, I think the early to mid 1990s, that I began to get an idea of what it was going to take to support the collection. Although I participated in fundraising in early years, giving tours to donors, writing NSF grants for specific projects, etc., this did not become one of my main responsibilities until I became Director in 2002.

How has your strategy for securing funding evolved through the years?

We have done many more collaborative projects in recent years—and we have also placed more emphasis on outreach, to the public and to students of all age groups.

What is one of your most successful projects that has been funded?

I guess I’d have to say that our original grant for specimen digitizing was our most successful project, back in the late 1990s. We were funded by the Xerox Foundation. They provided funding for a team specializing in imaging technology at the Rochester Institute of Technology to develop a protocol and equipment list for imaging herbarium specimens, and then they bought us the equipment and gave us funding to hire a staff member to do the imaging. The experience we gained through that project allowed us to apply for tens of millions of additional funding for specimen digitization.

Is there a particular direction that you would like to see the NSF go in with regard to funding herbaria? Is there a particular funding need that you see across herbaria, which is going unmet?

I would like to see NSF support a National Collections Action Center, which would support continued digitization efforts, support the development of linking collections through an Extended Specimen Network, provide ongoing workforce training and tools for collections to carry out strategic planning, and to evaluate their success through metrics that can be applied across all collections. I’d also like to see a larger budget for collections improvement, and another ten-year program, like the Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections program, that would fund ongoing efforts to digitize and link collections for a wide range of research applications.

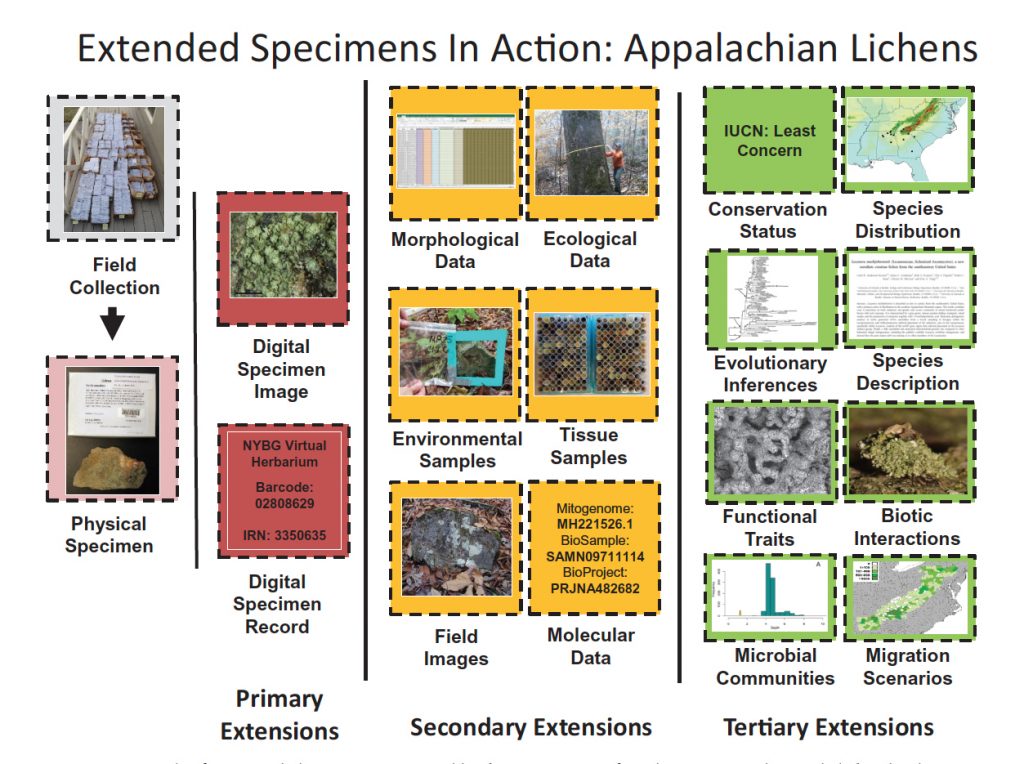

Can you speak further about the Extended Specimen Network and where you would like to see databases like iDigBio, GBIF, and WFO in 10 years from now?

As one of the authors of the Extended Specimen Network plan, I’d very much like to see this to be the central organizing principle for specimen data repositories going forward. We have to develop standards and protocols for linking specimens with one another and with their components, derivatives, research syntheses such as publications, and then we need to develop new ways of searching the data that are accessible to the wide range of potential users. In 10 years, I’d like to see the mechanisms in place for creating these linkages, and for it to be possible for new collections to flow seamlessly into the ESN.

Do you think collaboration between herbaria and botanical libraries is a potential component of actualizing the Extended Specimen Network?

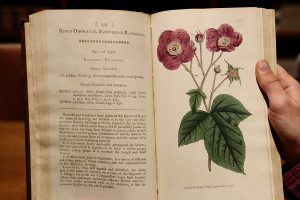

Yes, absolutely. The Library community has been very proactive in the digitization of their biodiversity content, through the Biodiversity Heritage Library, and we should definitely build on that, plus also focus of the digitization of archival material, like fieldbooks or fieldnotes and link all of these to the actual specimens. I’d love to see the day when one opens an article from BHL and for every specimen mentioned, finds a link to the digital record for that specimen!

Where do you see the role of multi-institutional collaborations as natural history collections move into the future?

Collaborations are absolutely key to the future success of natural history collections, in my opinion. The past decade has seen an unprecedented amount of collaboration, mostly related to the structure that NSF put in place for the ADBC program. But, we need lots more. There are many interesting possibilities for colaborations across institution types, and even between living collections and traditional natural history collections. One problem that inhibits the broadening of collaborations is that we don’t have a comprehensive registry of all U.S. biodiversity collections. If it was possible to find all collections of a given type, or in a given area, we might discover many new possible collaborations.

Are there any new funding agencies that have recently directed their support toward natural history collections?

Not as many as I would like to see. But, the importance of herbarium specimens in climate change and genomic-level research on plants, and the life that depends on plants (which is all life!) does hold tremendous potential for expanded funding for natural history collections. What we need more of is partnerships with research teams that use collections-based data in so that support for the collection is built into the original proposals.

What are some words of wisdom that you might share with collection managers seeking funding for their collections?

I firmly believe that looking for additional ways to make an herbarium relevant to its institution, users, students and the general public is as central to the day-to-day management of the collection as specimen mounting, filing and sending loans. To find opportunities, herbarium staff must keep informed about national and international biodiversity issues, participate in collections organizations, list servers and social media, and when possible, attend as many collection-related conferences or workshops as possible. Learn about what other collections are doing to demonstrate their importance and see if it can be adapted to your collection. It’s a lot of work, but managing an herbarium has never been easy, and is not likely to get easier over time!

Barbara Thiers is the Vice President and Director of the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at The New York Botanical Garden. Thiers recently published Herbarium: the Quest to Preserve and Classify the World’s Plants through Timber Press.